It has been almost two weeks since we left port in Bermuda. For me, it took about a week (the entire transit), to adjust to life at sea. Four days after being on the ship I would still wake up in the morning, get out bed, and fall over, caught off guard by the rocking motion.

Now that we are on-site and are diving Alvin and Sentry every day, ship life has become routine—at least as routine as sending a human-occupied submarine and a robotic underwater vehicle 2.5 miles below the ocean surface each day can be.

The mornings begin with Alvin launch. At 8:00 a.m., Alvin goes in the water with a pilot and two science observers. We watch as our friends climb into the sub, are craned overboard, untethered from the ship, and bob in the water for several minutes before starting their descent to the bottom.

After launch, the remaining science team gets busy. We process the rocks and sediment from the previous day’s dive, edit photos and video from the sub, plot Sentry maps, and plan and discuss the next day’s dive. It takes the whole team to make the science possible.

Alvin returns to the surface around 5:00 p.m. each day. The recovery is as impressive as the launch and we welcome our colleagues back on board with handshakes, smiles, and questions about what they found. Alvin brings back treasures, too—a basket full of rocks and sediment. We treat the rocks with care because they are key to testing hypotheses about the origin and extent of “popping rocks” and, perhaps, to understanding how much carbon dioxide is in Earth’s mantle.

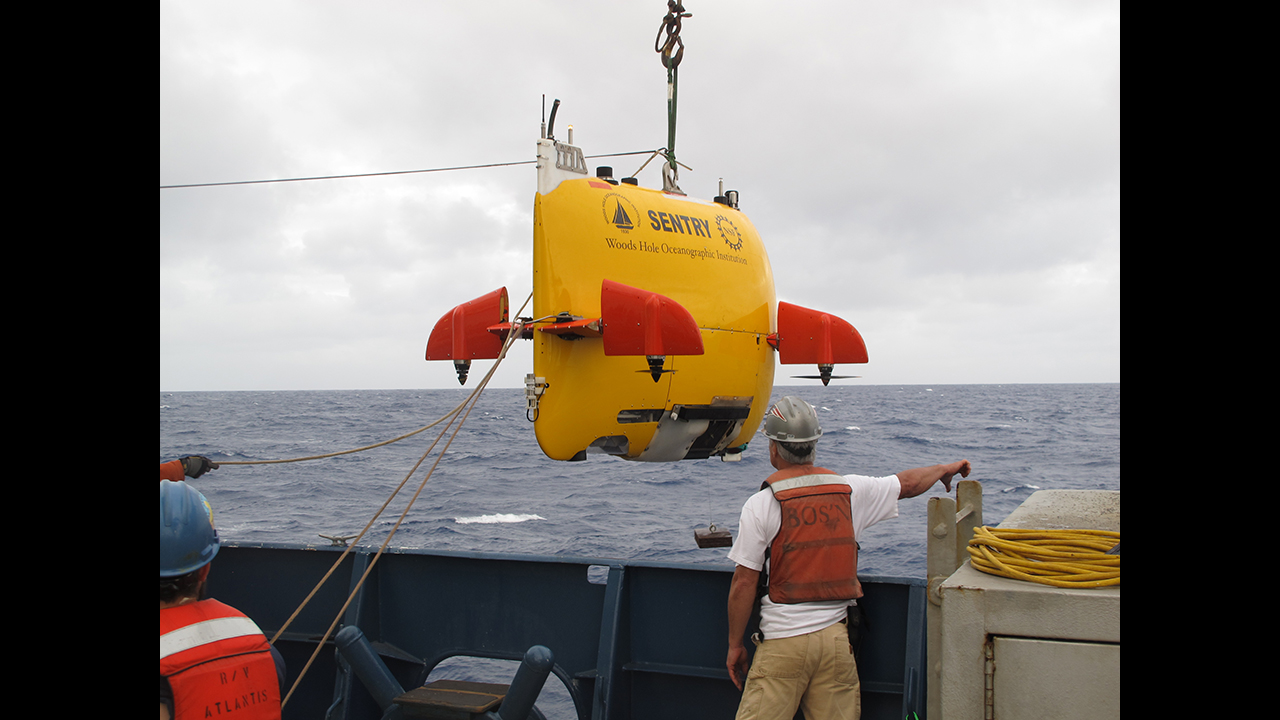

Sentry, an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) that creates high-resolution maps of the seafloor, is launched around 6:30 p.m. During the night, Sentry cruises close to the seafloor as it sends and receives acoustic pings that allow it to determine precise distances to the bottom. Shortly after dawn each morning, Sentry is brought back on the ship and delivers its payload—unmatched measurements of seafloor bathymetry and topography.

Breakfast marks the completion of a 24-hour cycle and our routine begins again. Alvin goes back in the water. Sentry data becomes a map that allows us to identify previously unknown hills, ridges, basins, and craters. Rocks collected the previous day pop (or don’t).

Our routine is exciting because each day we make discoveries. In the evenings, the day’s Alvin observers share what they found and we debate where to go next. As a result of our daily cycle, the science becomes dynamic. We plan each dive, in part, based on what was revealed in the previous one. And, two by two, we get to personally visit the seafloor.