As Alvin and its three passengers sink toward the seafloor, a tiny cargo sits tucked away, out of sight. It’s a laundry bag, the kind made from cotton mesh, with a dozen or so Styrofoam cups stowed safely inside.

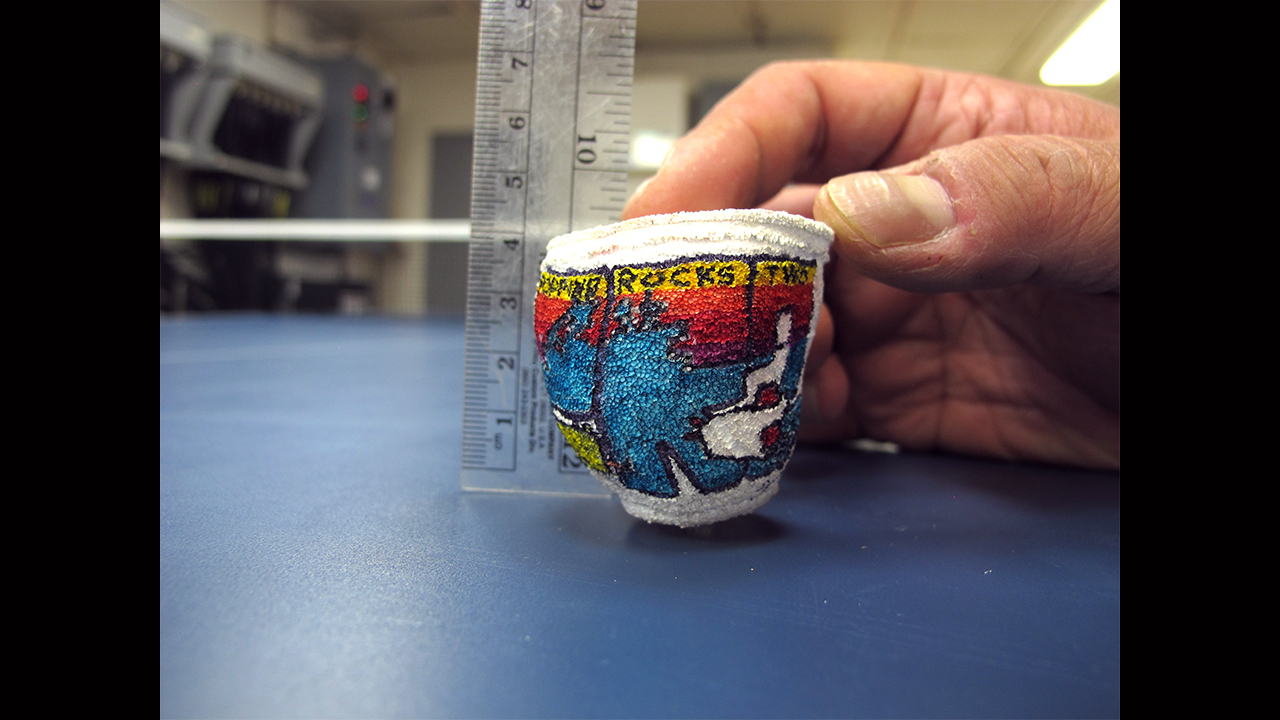

Each cup bears an image or design carefully drawn in brightly colored marker. Are these common household vessels being used for some kind of sampling mission? Is this a study on ocean plastics and their rate of degradation in seawater? No, the motivation for sending this picnic-lunch necessity to the bottom of the ocean is much more whimsical: they shrink.

Ten thousand feet below the ocean surface the surrounding pressure is immense. The weight of almost 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) of water bears down on the little sub 300 times greater than the atmosphere does at the surface. The pilot and two scientists are fine—they are protected by 3 inches of solid titanium. Our plastic passengers on the other hand, are subject to the crushing load of the deep sea. On purpose.

Styrofoam contains countless minuscule bubbles that contribute to its low density and excellent insulating properties. The bubbles are encased in a plastic called polystyrene. Under 300 atmospheres of pressure the bubbles are compressed into a tiny space and the framework of plastic around them is likewise squeezed.

The result? A sample from the dive that the chief scientists will let you take home (they get mad if you take their rocks); a small bit of proof that humans have reached the bottom of the ocean and a demonstration of physics in action: It illustrates the great pressure at the sea floor to children of all ages.

The Styrofoam tradition goes back to at least the 1980s, according to Dan Fornari, a Senior Scientist Emeritus at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and a seafloor exploration expert. Scientists make cups for themselves, friends and family, and outreach events. Fornari has shrunken hundreds of them himself and donated them to schools and museums, including the Smithsonian.

In truth, the cups are just a small part of an astonishingly elaborate operation to prepare and launch Alvin so that it can collect valuable scientific data. But the cups persist as a fun and educational shipboard activity—along with soaking first-time divers with chilled water.

There is something oddly romantic about designing a unique cup and using the ocean and Alvin to put a unique and indelible mark on it. It offers variety, color and character to each dive. And for the researchers who make the trip, the souvenir of a lifetime.