Let me set a scene. Perhaps an airplane might be best. You are sitting in your seat and your fellow row mate is surprisingly chatty. He or she wants to know where you’re going, where you’re from, and then the next question: “What do you do for a living?”

It is a question that many a mariner across the world has met with trepidation. We don’t mind sharing what we do, but we’re hesitant of the conversation that follows. Maybe it’s because we know there will be A LOT of questions headed our way. Maybe we don’t want to talk about ourselves. Maybe we’ve just gotten off a three month rotation and work is the last thing we want to talk about. Maybe it’s all three. Generally the very friendly stranger wins out with their persistence, and the hypothetical (and abridged) conversation follows:

“What do you do for a living?”

I work as a navigational officer aboard a research vessel.

“So you’re in the Navy?”

No, I am not in the Navy. People can earn their licenses for sailing two ways. Some of us go to a maritime academy for college, or some of us start as Ordinary Seaman, and work our way up the hierarchy by accumulating time at sea and taking a series of classes and tests to prove our competency. Many people also enter the Merchant Marine after years of service in the Coast Guard or the Navy.

“So, research. What kind of science? Where do you go?”

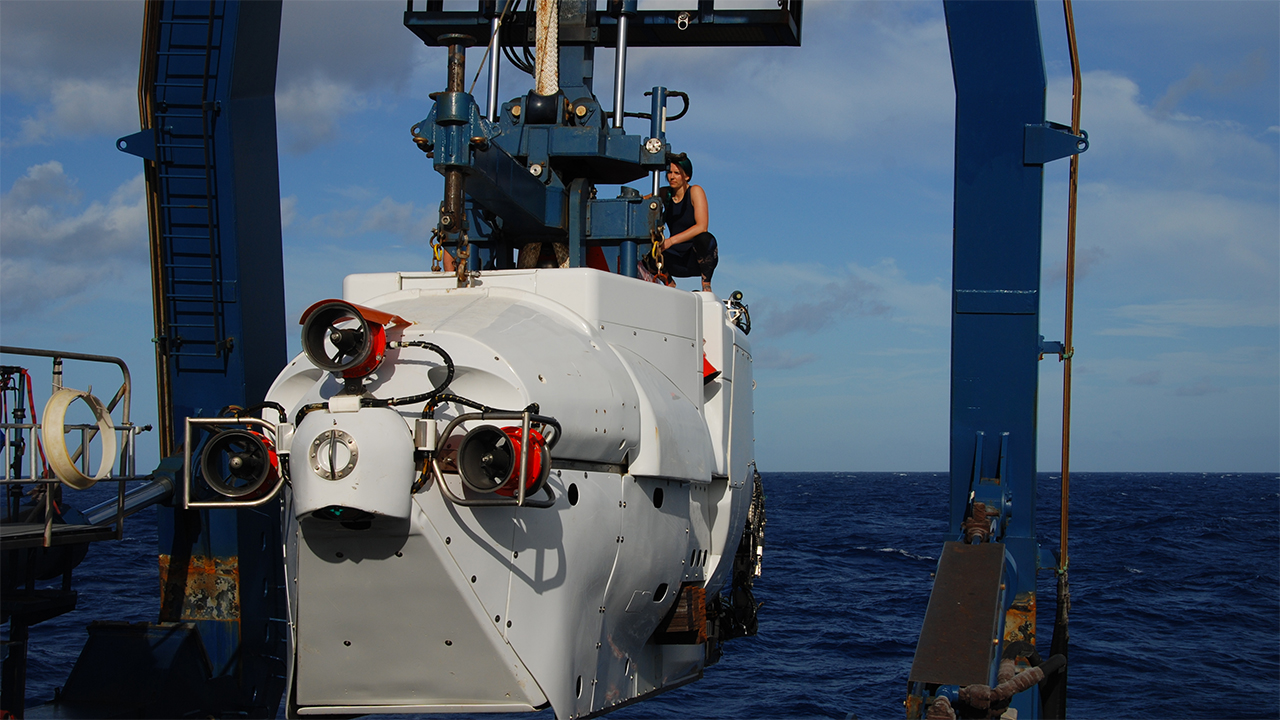

We have all different types of scientists from all over the world who do all sorts of specific science. Biology, chemistry, geology, and lots of science specialties that I can’t explain. My ship, the Atlantis, can go all over the world except where there’s sea ice. Each science group that comes onboard picks a place they’d like to study and the vehicles they would like to use for their missions. We are the home ship of Alvin, which is a human-occupied submersible. Science groups often come to the Atlantis to use Alvin, but we can also do basic oceanography, like make maps, do water profiling, dredge, take core samples, lay and recover buoys, and we can also take on a remotely operated Vehicle (like ROV Jason) or an autonomous underwater vehicle (like AUV Sentry), or really anything scientists can come up with!

“Wow that’s really cool. So like, what do you do?”

As an officer of any ship, we are responsible for standing a watch at a specific time of day for our entire work rotation. I work from midnight to 6:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m. on the bridge. At that time, I am responsible for the safe navigation of the vessel, and the safety of the people aboard. Generally, we make sure we are going the right direction and that there’s nothing in our way. We are also responsible, with the help of the Captain, to deploy or recover whatever instrument the science group needs to use.

“Wait, there are probably not a lot of women who do that, right?”

Actually, on the Atlantis we have several women crewmembers. I work with a Chief Mate, two Third Mates, a Steward and an Able-body Seaman all of who are women. It is a male-dominated industry, but more and more women are sailing.

“Isn’t it hard being away for three months at a time?”

Yes, it is, mainly because we miss events with friends and family. It’s also really nice getting three months off to make up for that or to travel. I don’t know many other industries that have that much vacation time. It’s definitely a big perk of the job.

“What’s your favorite part of your job?”

That’s a really hard question. The coolest part of my job is getting to swim as a support swimmer with the DSV Alvin. It’s really fun to get into the water and it looks great in photos, but that’s a very small part of my job. I think sunrises are a favorite part of my job. They are always beautiful. Ship handling during launching and recovering equipment is really fun. Meeting all the different scientists from all over the world and working toward a common goal for science that can benefit the world is pretty cool, too.

At this point, a friendly flight attendant usually asks what we would like to drink, and our hypothetical conversation ends. There may be many more questions spanning all sorts of topics about sea-going life, or maybe the above satisfies the stranger’s curiosity. You can then go back to your hypothetical book on your hypothetical flight, feeling pretty good knowing that people are interested in what you do.