(Mark Kurz, chief scientist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; Eric Mittelstaedt, co-chief scientist, University of Idaho; Funder: NSF; ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Prepare to get up close and personal with some deep-sea rocks!

The “popping rocks” that we were looking for (and found) come from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This area made up almost entirely of volcanic rocks called basalt because the seafloor is slowly spreading apart, and continuously erupting new lava, at least on geologic timescales. The gases trapped inside these rocks hold information about the interior of our planet—and that’s why we’re so interested in them! Let’s take a look at how we welcome these rocks from the deep to life on the surface.

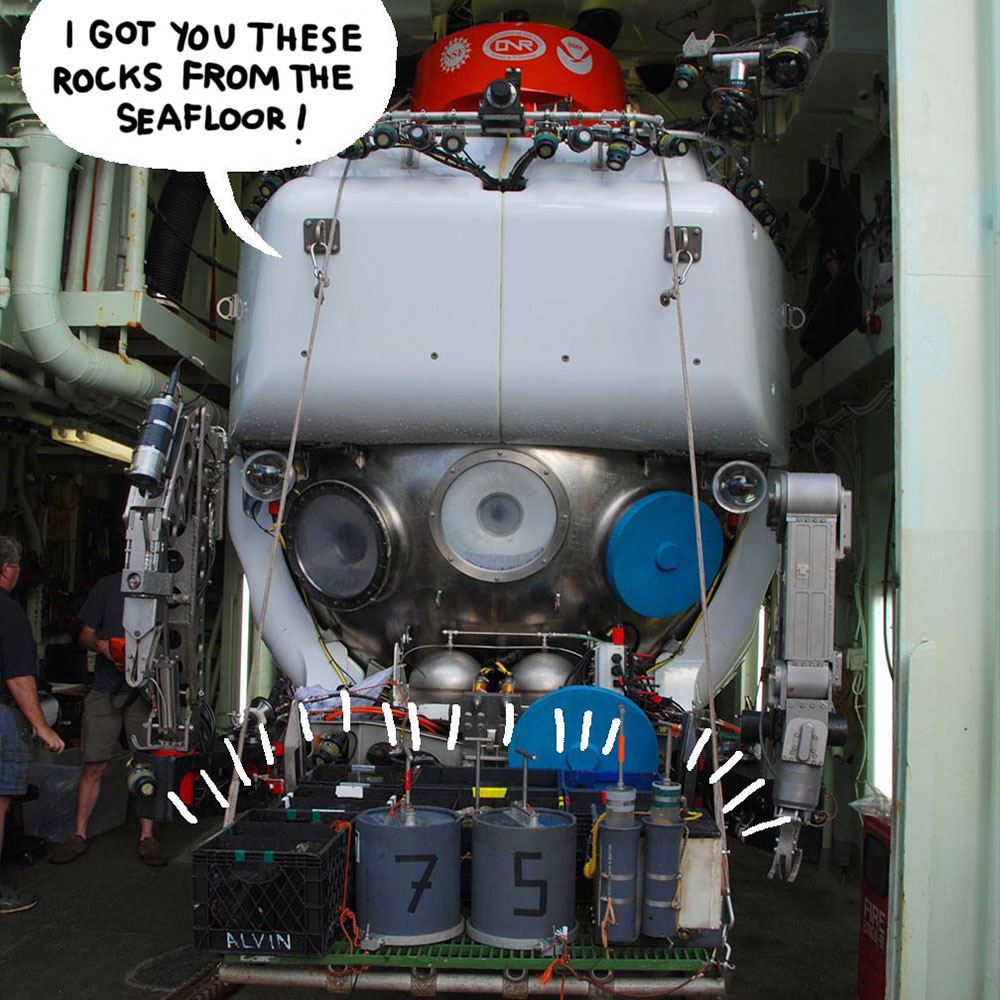

First we have to get the rocks! DSV Alvin dives to about 4,000 meters (about 13,000 feet) to reach the seafloor where the pilot and scientists identify types of basalt that they want to sample. Alvin uses its robot arms to collect the samples and store them in baskets (above).

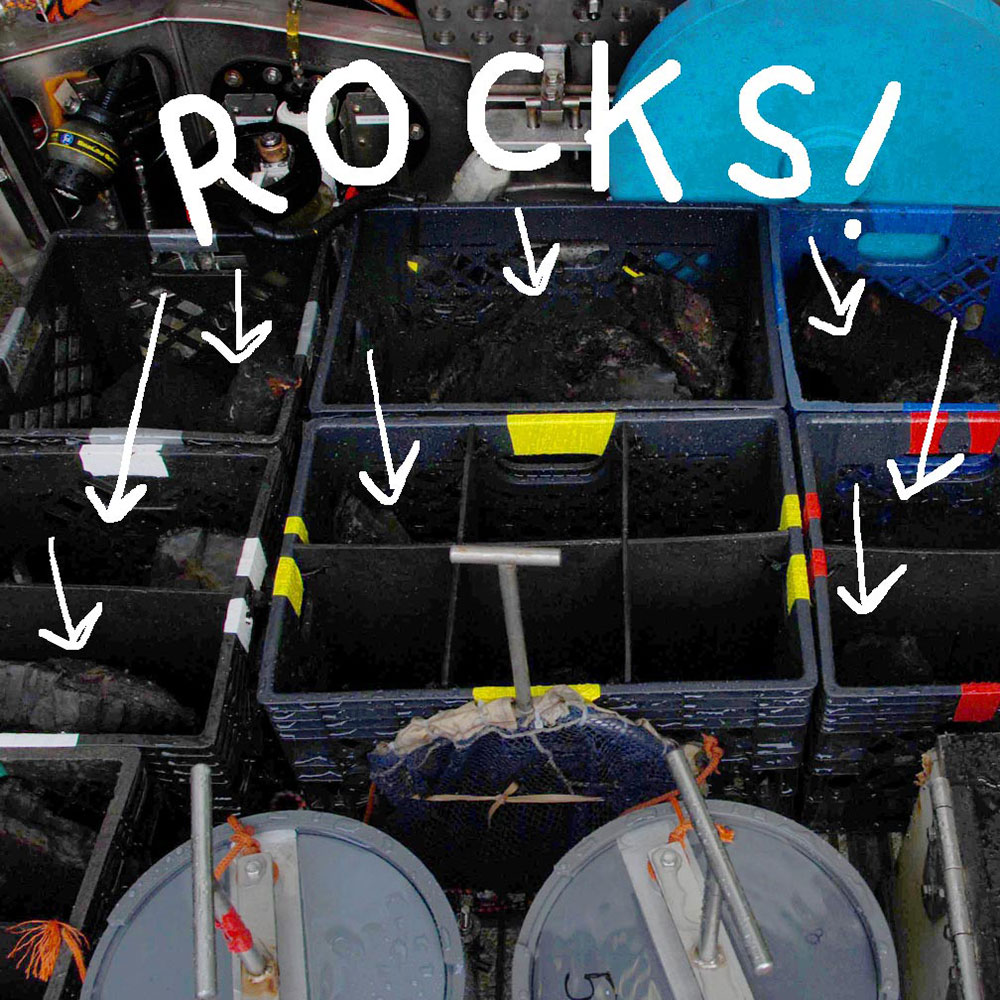

Once Alvin is recovered and secured, a plethora of excited geologists descend upon the basaltic bounty:

So many rocks!

Each rock is given a freshwater bath:

And placed in a numbered bucket:

The buckets are then transported to the Main Lab:

Each rock is weighed:

And then analyzed:

Okay, not that type of analysis. It’s more like this:

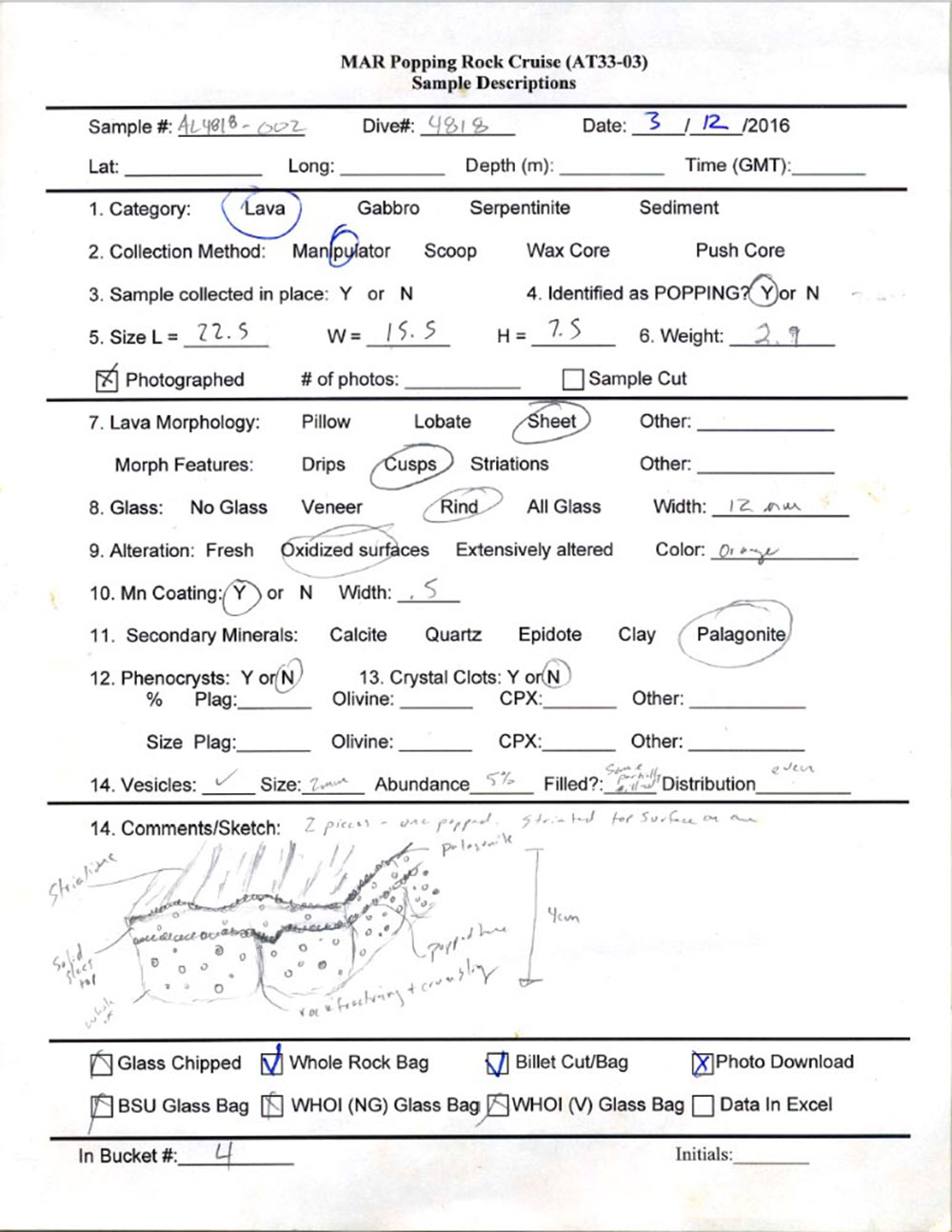

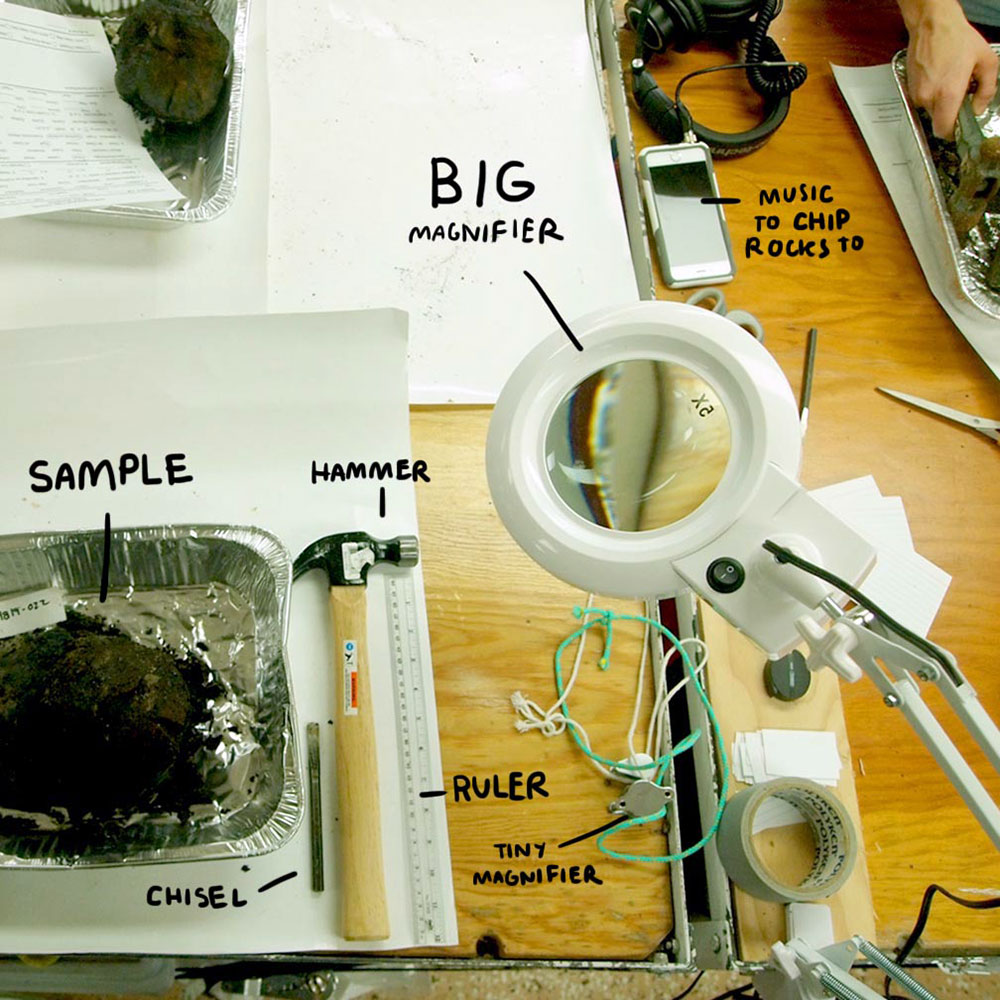

Here, we record characteristics like size, thickness of the glassy rind, amount of bubbles, types of crystal, and any other important features.

The rocks are then photographed:

Once photographed, the glassy rind needs to be chipped away from the basalt. This is one of the parts that we’re interested in analyzing back in labs.

And this is the glass-chipping station:

The glass is chipped off by placing a chisel at about a 45º angle from the rock’s surface, and tapping with a hammer.

This loosens larger areas of glass:

After most of the glass has been removed, the rest of the rock is cut into slabs with a rock saw:

And then placed under some heat lamps to dry faster (this will help us with the next step):

The dry slabs of rocks are examined under a microscope to look for minerals like olivine, which can trap little blobs for magma from the early stages of the rock’s life:

The rocks are bagged by sample number, and then placed in buckets for transport after the cruise:

Coming soon on the blog: how these deep-sea basaltic rocks are formed!